by

I Peccati

by Johan Creten

2020

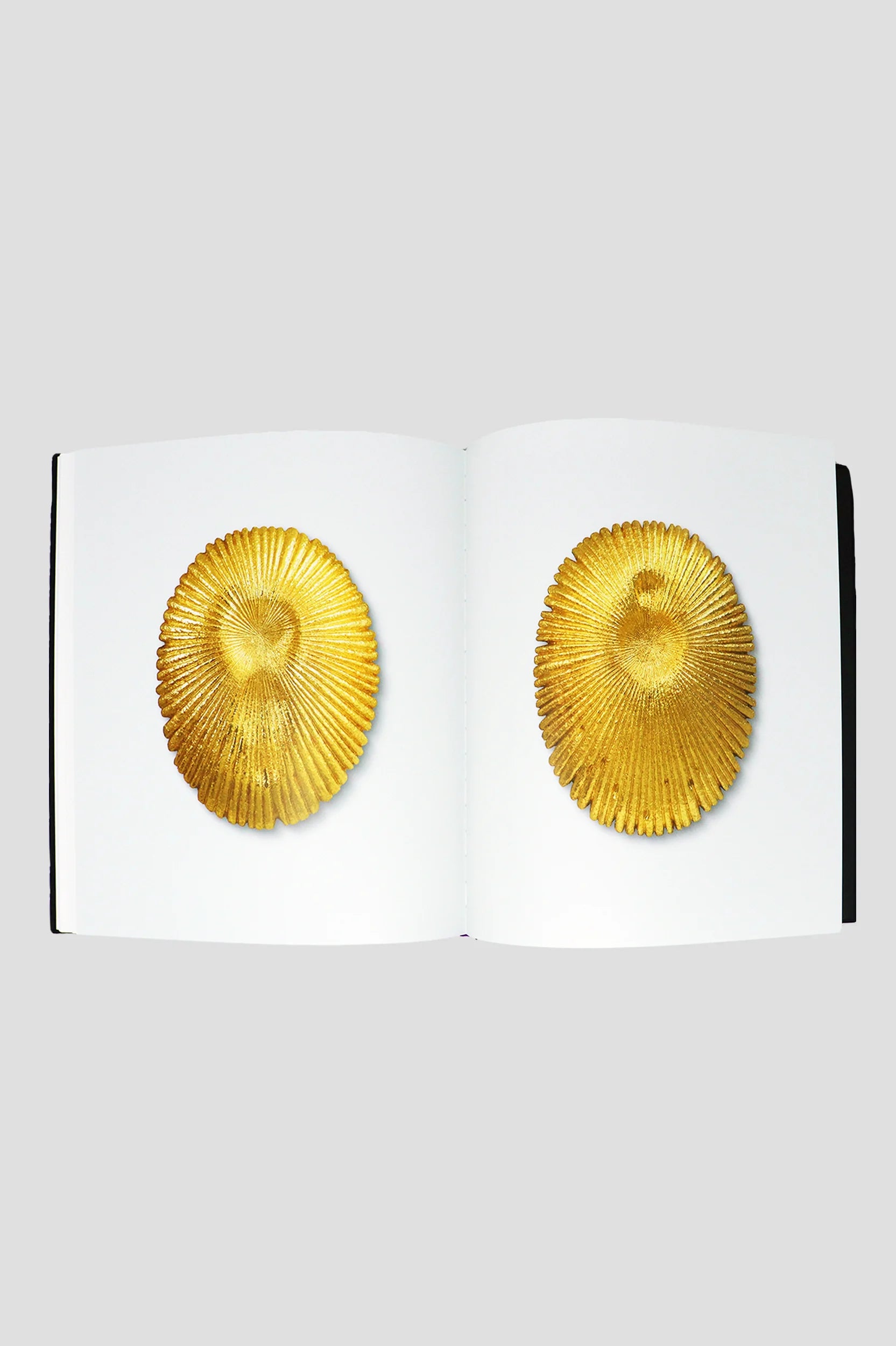

The exhibition “I Peccati” brings together, for the first time and with such breadth in Italy, a collection of fifty-five works by the artist, in bronze, ceramic and resin. They will be reunited and juxtaposed to some historical works by Lucas Van Leyden (1494-1533), Hans Baldung (1484-1545), Jacques Callot (1592-1635), Barthel Beham (1502-1540) and Paul van Vianen ( 1570–1614), milestones underlying Johan Creten’s thinking.

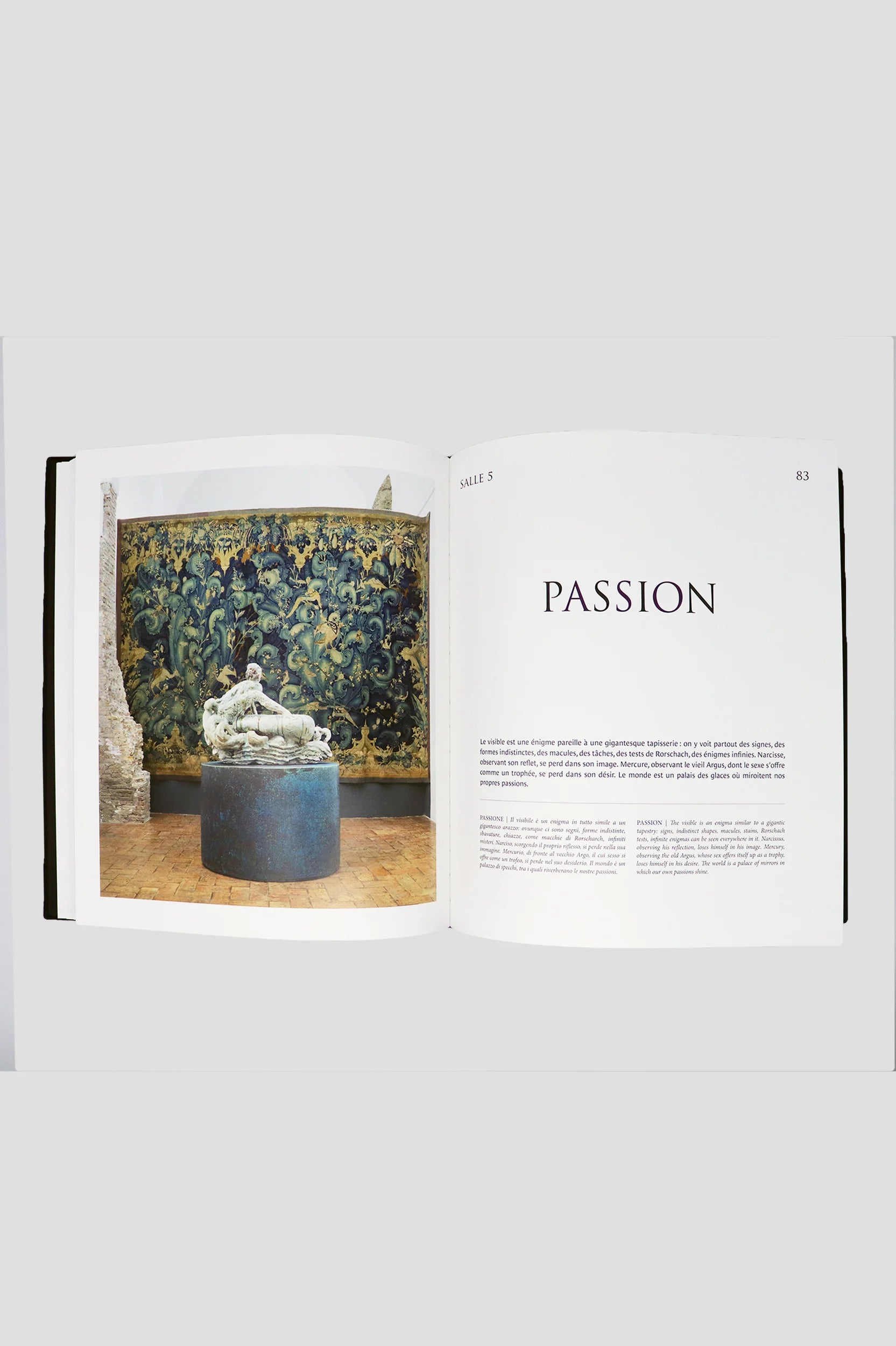

Johan Creten mentions 'Slow art' and the need for a return to introspection. A movement, ranging from miniature to monumental figures, which allows you to take time and immerse yourself in an exploration of the world with its individual and societal torments, for a journey filled with surprises and emotions. The sculptures of Johan Creten made especially for the exhibition between 2019 and 2020 added to the pieces that punctuate his journey from the 80s to the present day, are associated here with 16th and 17th century prints, tapestries and bas-reliefs from the artist’s personal collection. These historical works summoned by the artist are a real reference in his creative process. They reveal his concerns, be they artistic, historical, political or philosophical. The intersection of these works in the exhibition upsets our perception through multiple reading points of view which, from the past, question the future of our humanity.

'With Johan Creten, the sins are not seven in number. Seven, this implacable number, the same as the Bible’s sacraments and Rome’s hills. Here, the sins are infinite and unlimited, inexhaustible. They are not numerable, but just designatable. Sins are not all capital, they can be imperial, imperious, peripherical, insidious, insignificant, invisible. They are always below calculation and language. The seven capital sins are little when compared with silliness, barbary, boredom, mutilation, regret, melancholy and terror, in short, with life. Thus, Johan Creten’s sculptures have nothing to do with moral or sanction, guillotine or censorship. They speak of sins, of life that merges desire and pain, hope and misery, luxury and anger, love and death, Eros and Thanatos. They speak of amphibian life, between the Styx and Paradise. They speak of instinctive life, when hearts beat, when sneaks coil, when wings deploy, when vulvas gape, when the curtain moves and the naked truth emerges from it, at last, that hypnotic Medusa.

May sin not be, after all, the tired form of purity? Does it not point to our condition of extremely fallible men? Is sin not, to quote Victor Hugo, a beautiful “gravitation”? '

– Colin Lemoine, art historian

Kindly note that for purchases made outside the European Union, taxes and import duties are not included in the listed price and will be the responsibility of the buyer.

All limited edition prints are sold unframed unless otherwise specified.